Understanding How We Connect to Games Could Change the Way We See Our Lives

Daniel A. Kaufmann, Ph.D.

Owner of Area of Effect Counseling & Dr. Gameology on Twitch

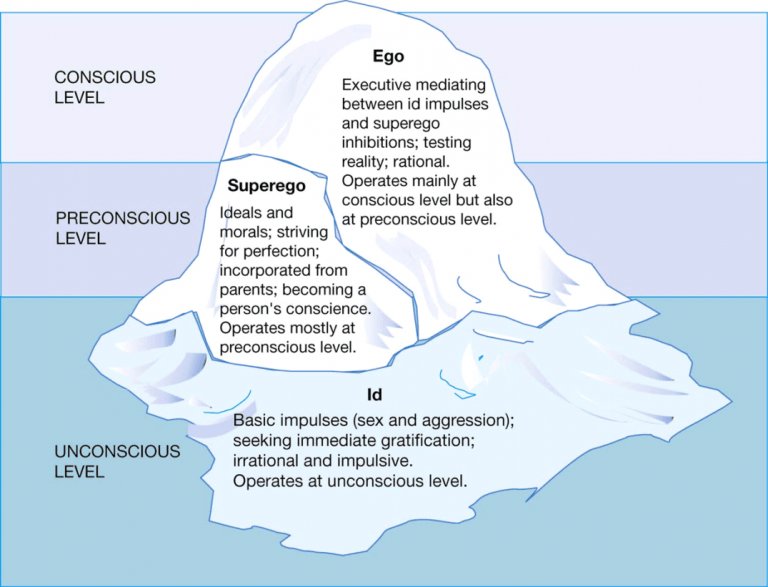

Icebergs have often been used in psychology to convey the idea that we can see something worthy of amazement and still not really understand all of the intricacies at play in the phenomenon. Life offers many scenarios where mental health awareness can present an advantage for our insightfulness, and I have often found in those settings this metaphor can be useful. The most common uses for this symbolism come during conversations about early psychological theories a la Sigmund Freud or Carl Jung. However, the idea of the unseen shifting the purpose of what appears to be obvious can usually add nuance whenever an interpersonal dynamic creates a multi-layered response from the individual in question. Since our games can do this as well, I thought I would take some time to explore how this works with games. Since games can more easily create an in-depth experience for a wide range of people, I think it could be a useful metaphor we can use to shed some light on how we can function at our highest levels and benefit the most from our life ‘EXP’eriences.

Podcast: The Gaming Persona – Episode 3

Connecting Procrastination with the Psyche

The iceberg model is frequently the starting point for explaining the line of separation between the conscious and unconscious portions of our personalities in the Freudian theory of psychology referred to as psychoanalysis (Blasko, 1999). The higher into the sky the iceberg extends, the more aware a person would be of these components of their thoughts. Freud conceptualized this as the ego, the place where the conscious decisions are made. For game players, we would hope this is the part that makes the final decision to play a game, as this part of the psyche settles the score when the superego and the id are at odds with each other. The superego represents the part of the mind which knows the ideal situation where gaming should be “allowed,” while the id is the part of the mind that just wants to have fun at all costs. When we procrastinate, the id wins battles it should not win, convincing the ego that the superego’s position that “now is not the right time” is just being overly cautious (Urban, 2016). We play when we should not play and push off the hard work that leads to a higher level of calm and personal satisfaction down the road. The superego exists in the preconscious, and so it provides the least personal perspective. It simply sticks with “what is the right thing to do?”, and given what we see in the world today, it probably doesn’t succeed as often as we wish it would on the personal or societal levels. So, we decide to play games where there is a better chance the superego can be satisfied by our own personal-level decisions (and find the real power of games in our lives when they are healthy).

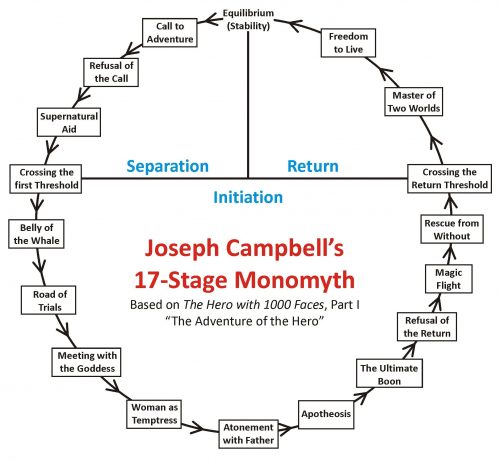

The Psychological World = The Special World in Campbell

The monomyth (commonly known as the Hero’s Journey) is a term we use to identify in our stories the concept that each hero we follow through their struggles and triumphs is experiencing the same story with different details (Campbell, 1949). This concept is refined across the works of Joseph Campbell (1904-1987), a mythologist who spent his life teaching classes, lecturing, and researching the world’s stories, religions, and myth to find the common themes in what we are searching for from civilization to civilization across all of recorded history. In order to share the modern story of myth, Campbell reviewed his ideas numerous times with those who assisted in the movement of the medical model to include an awareness of human psychology, namely Sigmund Freud, Carl Jung, and numerous others we learn about in our intro to counseling and psychology courses. While the action inside video games frequently depicts the abilities of our heroes and villains to use powers from the special world, I have recently begun to look at video games as a way to see a reflection of these magics as our wishes to fully understand our psychological world. After all, when a person is sitting next to me and asks why a certain behavior happens for them in a certain way, it does feel somewhat transcendent to remind people of how the brain works region to region, and how our personality is also the manifestation of neurotransmitters firing from place to place, resulting in what we perceive as our very personal experience of our own personality.

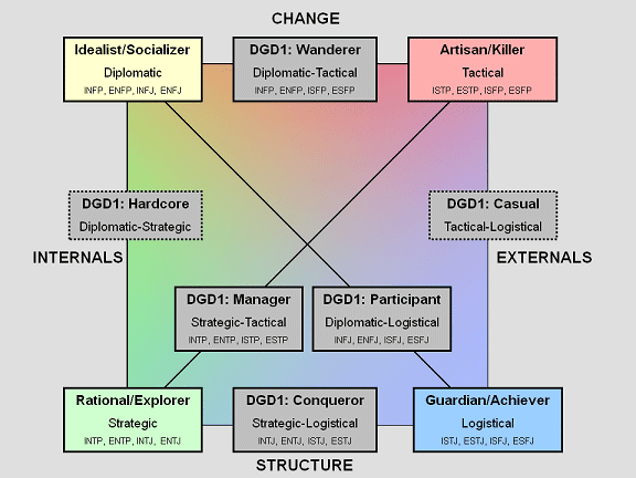

The Tip of the Game Development Iceberg: Player Personalities

Video games are developed with an understanding of which types of players will enjoy which forms of content. The move from the unconscious model of personality over to a more assessment style understanding began with Jung’s separation from Freud and developing an understanding focused more on archetypes and orientations. While this led to new ways of understanding tendencies inherent in socialization and decision making, it also paved the way for what we now know as personality type. Whether you enjoy the five-factor model or a type-based design, personality as a concept owes a lot to these 20th century disagreements and the resulting outside-the-box-thinking to create concepts which are far easier to apply during a random conversation. In games, research has found that it is possible to identify who will play what content with which levels of enjoyment using these very concepts of personality (Kaufmann, 2016; Yee, 2006). There is still room to vary from person to person, but game companies know all too well who will play what when they add a new feature or make new design decisions. It would appear the subconscious portion of that iceberg is a surprisingly accurate way to build your video game…

Is This Good for My Kid to Play?

This question comes up a lot in my line of work, and the idea of what is alright for children to play comes down in large part to several things. These can be simply listed as:

- Your understanding of the games they are playing.

- Your stance on content and age-appropriateness.

- Your ability to have teaching moments with your child to learn about their gaming motivation.

- How well you are able to teach that life motivation can be the same thing as what we use in games to succeed if we take the chance to think about the common ground between the two.

The hope that we can follow a checklist mechanically and achieve success is certainly reminiscent of my same dreams every time I get stuck on a difficult boss fight. However, in this case the recommendations are designed to help parents understand the difference between raising with a generalist or specialist philosophy for your child. CNBC reviewed some of this in a blog series which focused on parenting insights and how to help us all raise more exceptional children (Mehta, 2021). To summarize, it seems that playing to your strengths, learning how to strive for excellence, building confidence, developing patience, specializing your skills, and always seeking to improve are the ways we aim to parent children effectively. Ironically, I know for myself I learned all of these from a mixture of video games, movies, comic books, sports, martial arts, and my friendships. The final point I specifically remember is that my parents had frequent talks with me to make sure I wasn’t going to become a deviant-ninja-assassin like so many of the characters I would play in early 90’s video games. Yes, you can all imagine the parents of 7-year-old Dr. Gameology asking if I felt like completing a Mortal Kombat Fatality on somebody. Still, those conversations did happen, and we have blogs like this to thank for it. The silver lining is that the benefits of those conversations helped me to understand that A) I need to always get my schoolwork done before I play games, and B) I am not the characters I play as in video games.

What We See and Do Not See in Video Games

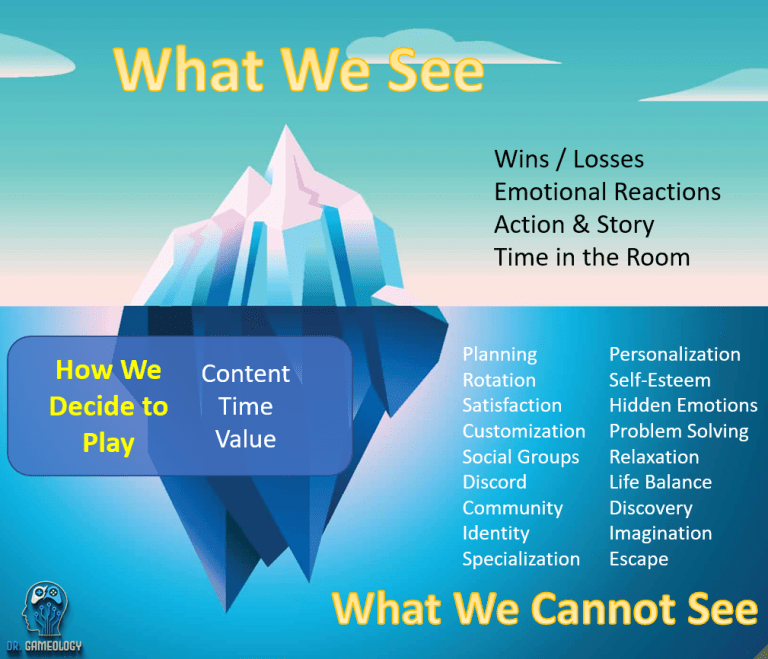

The reality is that there is no one blog post I or anyone else can offer which will answer all of these simple questions in a simple way. This speaks to how much of the video game experience really does fall in the unconscious part of what our eyes can see, and our mind can process, when we play a game (or watch a game being played). I will attempt to share in the image below a few of my thoughts about why this is. Basically, we can plainly see what happens we watch a game being played. However, the player is experiencing so much more than what can be categorized by the outside watching from their couch.

Much like the line we draw between conscious and unconscious awareness, a game player is experiencing a steep orientation task whenever they play a game. Hundreds of tiny decisions are being made every minute of gameplay. The persona is absolutely involved in these decisions and their consequences. We are learning a new story and becoming a part of it. We are finding our strengths every time we experience the conquering of an obstacle. We are seeing evidence that we can transcend our limitations every time we fall short and then progress to the next step. The list of options available in some of the more advanced games we can choose to play are offering many different opportunities to us all the time during play. We experience agency over our own time where we get to choose the best way to spend our day (or at least the next hour). These are the things we experience in life as well. Whether we are a parent or child, player or viewer, we often lament that we do not talk about the life we are leading anymore because we are playing games. This disappointment distracts us from the opportunity to see deeper into the implications a game gives us to ponder. Humankind has always told stories with the best technology available going back through early 1900’s Hollywood all the way to ancient Greece, cave dwellers, and beyond. We do this now with videogames, comics, movies, social media, and the like. I am optimistic that the more we learn to embrace the history of the psyche by connecting with ourselves through games, the more time we will take to notice the answers are right there in front of us. All we have to do is see deeper into the depths to notice that the rest of the iceberg is happening too. This is how we shift our focus from what we cannot see to noticing the range of things we pass through as we explore the full story for EXP gained in life.

References

Bateman, C., & Boon, R. (2006). 21st century game design. Course Technology.

Blasko, D. G. (1999). Only the tip of the iceberg: Who understands what about metaphor? Journal of Pragmatics, 31(12), 1675-1683. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0378-2166(99)00009-0

Campbell, J. (1949). The hero with a thousand faces. New World Library.

Kaufmann, D. A. (2016). Personality, motivation, and online gaming [Order No. 10246131, Available from ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global (1860872558). https://www.academia.edu/40102823/Personality_Motivation_and_Online_Gaming

Mehta, K. (2021). A psychologist says parents of ‘exceptionally resilient and successful’ kids always do these 7 things: ‘Yes, some are a little intense’. Raising Successful Kids. https://www.cnbc.com/2021/05/11/how-to-raise-exceptionally-smart-resilient-success-kids-according-to-psychologist.html

Urban, T. (2016). Inside the mind of a master procrastinator [Video File]. https://www.ted.com/talks/tim_urban_inside_the_mind_of_a_master_procrastinator

Yee, N. (2006). Motivations for play in online games. CyberPsychology and Behavior, 9(6), 772-775.